Margaret Begbie

National Fire Service

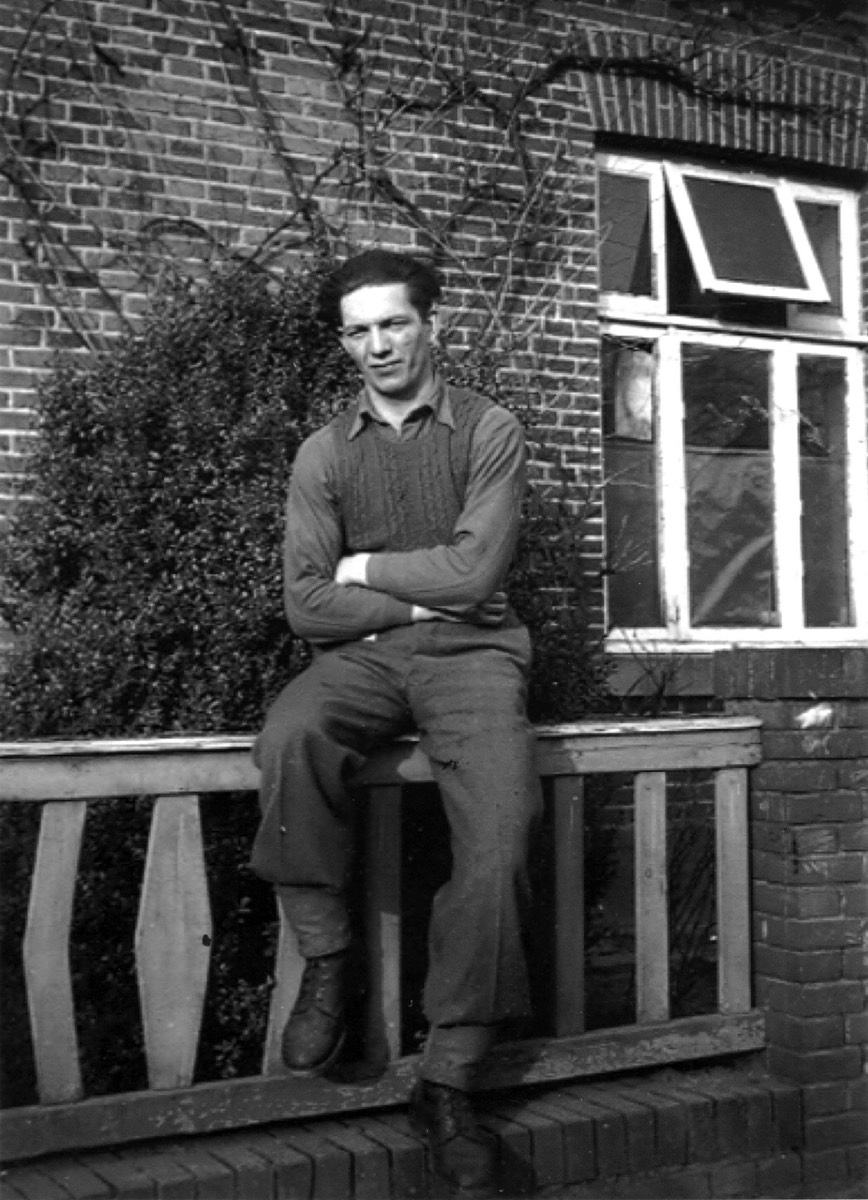

Tadeusz Brylak

Polish Army

James Drysdale,

Gunner, Royal Artillery

Tadeusz Brylak - Lance Corporal, 1st Polish Motorised Artillery Regt.

Interviewed in Longniddry on Monday 17th June, 2013, when he was 96 years old. This is a long story, not best designed for a website, but so interesting that it has to be included.

Early History - Internment in Romania

Tadeusz was born on the 12th November, 1917, in Kolacinek, a little village near Warsaw, Poland. Kolacinek was under Russian control then and the war was going very badly at the time. Tadeusz's father fled from Warsaw to escape Russian military service. When he was twenty-one Tadeusz did his National Service and later joined a regiment to train others in how to deal with Gas warfare in a barracks about twenty kms from Warsaw. War broke out and his battalion moved towards Romania. He was a driver and joined a convoy of trucks which could only drive through the nights, because of enemy aircraft, and which then hid in forests during the day. They showed no lights and the drivers drove in relay. They drove towards the south-eastern border of Poland (near Russia) but, at the time, Tadeusz had no idea where the convoy was heading. He was also curious as to what the convoy was carrying and he asked an officer what was in the large boxes in the trucks. The officer said they contained important state documents, but Tadeusz had no idea if that was true. He has since learnt that they might have contained the Polish gold reserves. The officer went away to find somewhere for the convoy to hide but returned with the news that the Russians had invaded Poland. The convoy escaped across the border into Romania and drove on to Bucharest. There they were ordered to leave the trucks and take their belongings out of them. Then they were taken in buses to a former school, now an internment camp, where he stayed for a month.

He was transferred to Tarkajune (sic), in the west of the country, to specially prepared buildings already containing a few thousand Poles. There were watchtowers and double barbed-wire fences all around the camp and it was patrolled by guards who would shoot at anyone who approached the strands of wire. Tadeusz arrived there in October and managed to escape around February. He believes his escape was a miracle but leaves us to decide for ourselves. Conditions in the camp were appalling, terrible, with almost no water. When water did arrive it came in a lorry and everyone had to run to get a bottle of water from the barrels on the lorry. The Romanians did very little to improve conditions, despite repeated complaints. They were allies of the Germans: Antonescu being a “Nazi”, according to Tadeusz. [Antonescu was executed after the war]

Around Christmas the British ambassador, or some such diplomat, came on an inspection but was only shown the best places. Conditions improved a little, especially access to showers. These were badly needed as the men were suffering from lice and the results of overcrowding in the cramped buildings where the men slept on boards in three-tiered bunks. They only had straw to lie on which, of course, crumbled to nothing. New straw was provided but food remained at starvation level.

Escape To Yugoslavia

After the new year the men were brought in groups to the town to a special train to have their clothes disinfected and themselves deloused. Tadeusz realised that they would have to walk to the town and that he might have a chance to get away. On the day he went there were soldiers everywhere so there seemed little chance to get away on the way there. However, there had been lots of snow and Tadeusz discussed running off with a friend.

As they returned from the train, walking along in a column, he could see two people coming towards them and at that precise moment a blinding snowstorm blew in and obscured everything. Everyone hunkered down and Tadeusz and his pal ducked out of the column and moved in behind the two men despite Romanian guards both in front and behind them. They let the column go past and then walked faster and faster to get away. They got into town and Tadeusz said,

“What are we going to do here? We haven’t got a penny and it’s terribly cold, frosty. What are we going to do now? Are we going to ask a Romanian for food, for shelter for a night? It’s risky.” He stood by a Barber shop window so that he could see the reflection of the police manning a check point at the end of the street and decided the best solution was to go back to the camp. He felt that if he’d stayed there he would just freeze to death. He then heard two men passing and speaking Polish so he caught up with them and told them what had happened and they said, ‘Fine. Just follow us.’

Many Poles who’d been in the army were allowed to live as civilians and they organised escape routes. Tadeusz followed them and they took him to the YMCA and then shut the door and gave him food and a suit of civilian clothes and told him to wait there. They contacted some Polish people and took him to them at night. He stayed with them for a few days and then one came in one night and said that tonight he and some others would gather at the railway station and then go to Bucharest. They went to near the station while this chap went to get tickets. Tadeusz said that,

“We just hid in doorways nearby and we waited and waited and waited but the chap didn’t come back, so we went to the station to find out what had happened. We opened the door to the ticket room to find this chap, the guide, with two policemen, so we shut the door fast and we ran!

The policemen followed us but we split and I don’t know how I managed to get back to the house because I didn’t know the city very well. After a couple of days men came and took us to the train, not at night but in the middle of the day. But we didn’t go into the station for tickets, the chap told us to wait by a little gate at the end of the platform and to wait until the train moved off and just jump on. We did that but we would have to change in Craiova and we would have had to get off the train to do this. Anyway, we two escapers were sitting in the carriage and along came the conductor and he took our tickets away with him.

Later I went and asked the conductor for our tickets but he wouldn’t give me them. I only discovered later that he expected me to pay him a backhander. But we’d only been given a very small sum to get by with and we couldn’t pay him. We had no money! If I had had I’d have given him ten bob or something like that, since we couldn’t show any tickets to get off the train. So police came and took me and my companion away to a police station. We stayed there for a week or so and then we were transferred to Craiova. One evening a policeman came in and told us to come out and we went to this commander’s office and he told us we were free! Someone in the escape organisation had taken us under his wing (I think he must have paid the commander) and this man was waiting for us and took us away to the station and got us on a train to Bucharest.

We arrived at Bucharest at night. It was dark and a man was walking along the platform calling ‘any Polish people here?’ and we just got out and followed him (there were a few of us) and we were taken to different houses, to Romanians. A chap and I were left with nice people. We stayed with them for a few days and they used to take us out at night for a walk, a bit of exercise. After that a chap called and gathered a group of us and took us to the station and we got passports which had been made up for us. We also got tickets and got on the train and were away. We were told that ‘from now on, you’re on your own!’

To France And Service In The French Army: April 1940

So we travelled to Yugoslavia to an important town whose name I can’t remember. We got through Belgrade and reached Split where there were at least a hundred other escapers. We stayed a week or so until a chap got us on board a Greek boat and we sailed to Marseilles in France, around Sicily. We had to register and when I said I’d been at a gas school they didn’t know what I was talking about so in the end I said put me in the artillery. So, they sent us, four of us who had been together in the boat, to St Nazaire, to Pontchateau. That was the end of March, beginning of April, 1940.

After that we didn’t get any arms or anything. We spent weeks just walking the streets because they didn’t know what to do with us. Then the Germans invaded France and very quickly some of us were formed into an anti-aircraft battery. But we didn’t know anything and just had to bide our time and they transformed us to an anti-tank battery. They gave us equipment, small anti-tank guns, but no one fired a shot from them. We didn’t know how to operate them: it was all too quick. We got a few trucks and I was allocated a motorbike and that was that. They gave us ammunition and also some for our personal use but after a few days some was taken away and then more. There wasn’t enough to go round and it was needed for our one machine-gun. We were left with twenty-five rounds and were sent to the north of France to stop the Germans with that! What were we going to do with it? It was a joke! Anyway, we travelled, carefully, we only had one wireless.

France Falls: Tadeusz Heads For Switzerland Then St Jean de Luz

France capitulated so the war was finished for us. What were we going to do now? Where were we going to go? The advice, rather than travel as a unit, was to get ten or fifteen, twenty men on each truck and to disperse, otherwise we would attract the attention of the Germans. So, we went our different ways and I chose the one I thought would be best. We had no maps and there were refugees everywhere. It was chaos. We came to a place where the road, both at front and back, was blocked.

We decided the best thing to do was to try to reach Switzerland. So, someone found a map and we went this way and that across France towards Switzerland and we made it as far a Dijon not far from the border. The local French told us that the Germans were already patrolling the border and we couldn’t get through there, so we decided to go to Bordeaux and get some transport there.

We arrived in Bordeaux but there were no ships to get aboard there: everything had stopped. We were advised to head south to Bayonne and we thought if we go that way we could go to Spain. But there was no transport when we reached there and we were told to head to St Jean de Luz, a little fishing village on the border where we could cross over into Spain. We arrived there late at night. It was winter and the lights were still on because the Germans were far away.

We were absolutely starving and we looked for somewhere to eat. We were stopped by a patrol of British sailors who stopped us and told us to go to the harbour where we could get a little boat to take us out to a larger one. We did this and reached the boat which turned out to be Polish. (The Stephan Batory) We travelled through the night with French, Belgian, Dutch, all sorts of nationalities. We could hardly find a place to sit down, it was so crowded. Someone said, ‘Now we go to America: the war’s finished for us’. We thought that was very nice but we thought that if we go to America we might get torpedoed because already the Germans were torpedoing boats.

Escape To Britain

We had a sleep and then, next day, we went on deck and found that we weren’t in America, My goodness, I said, we’re in Britain. I’d never been there before. They took us in trains to Haydock Park, the racecourse in Liverpool. There we found a lot of tents ready for us and we stayed there for about a week before we were taken by train to Crawford, in Lanarkshire, in Scotland. And it was raining, raining and the ground was a quagmire. We could hardly put our feet out of the tent. A while later we moved to Douglas Water and stayed there all summer until November when we moved to Arbroath.

1st Polish Motorised Artillery Regiment badge.

We were in the 1st Motorised Artillery Regiment, part of the Ist Polish Armoured Division, at this time, the time after Dunkirk and the Phoney War. We had Polish officers though we came under British control higher up. In Arbroath we were given seventy-five millimetre horse-drawn guns, very old, Napoleonic! I was driver to the Major who was the regimental commander. We went for exercises with the guns at the back of the lorry. But these guns were meant to be pulled by horses so the wheels came off when the lorries went too fast. So they gave us new wheels and the guns had to be loaded into the lorries, in the back, up ramps. Then they build shelters for two guns to be sited at HMS Condor, a naval airbase near Arbroath, in case the Germans invaded.

We went on a lot of exercises, training, which was all needed when we took part in the second wave of the D-Day landings. We bided our time, moving from place to place until we came to Gosford in April 1942 from the village at Glamis. This was the best of camps. There was a Naafi canteen, a Church of Scotland canteen, nice accommodation in wooden buildings with maybe thirty men in each. We had showers and a nice band and had dances every Thursday. We had to do something to occupy our time! Another dance place was in Port Seaton, at the Pond Hall. We were there in Gosford for almost a year.

Stationed in Gosford Estate, East Lothian

We went on a lot of exercises, training, which was all needed when we took part in the second wave of the D-Day landings. We bided our time, moving from place to place until we came to Gosford in April 1942 from the village at Glamis. This was the best of camps. There was a Naafi canteen, a Church of Scotland canteen, nice accommodation in wooden buildings with maybe thirty men in each. We had showers and a nice band and had dances every Thursday. We had to do something to occupy our time! Another dance place was in Port Seaton, at the Pond Hall. We were there in Gosford for almost a year.

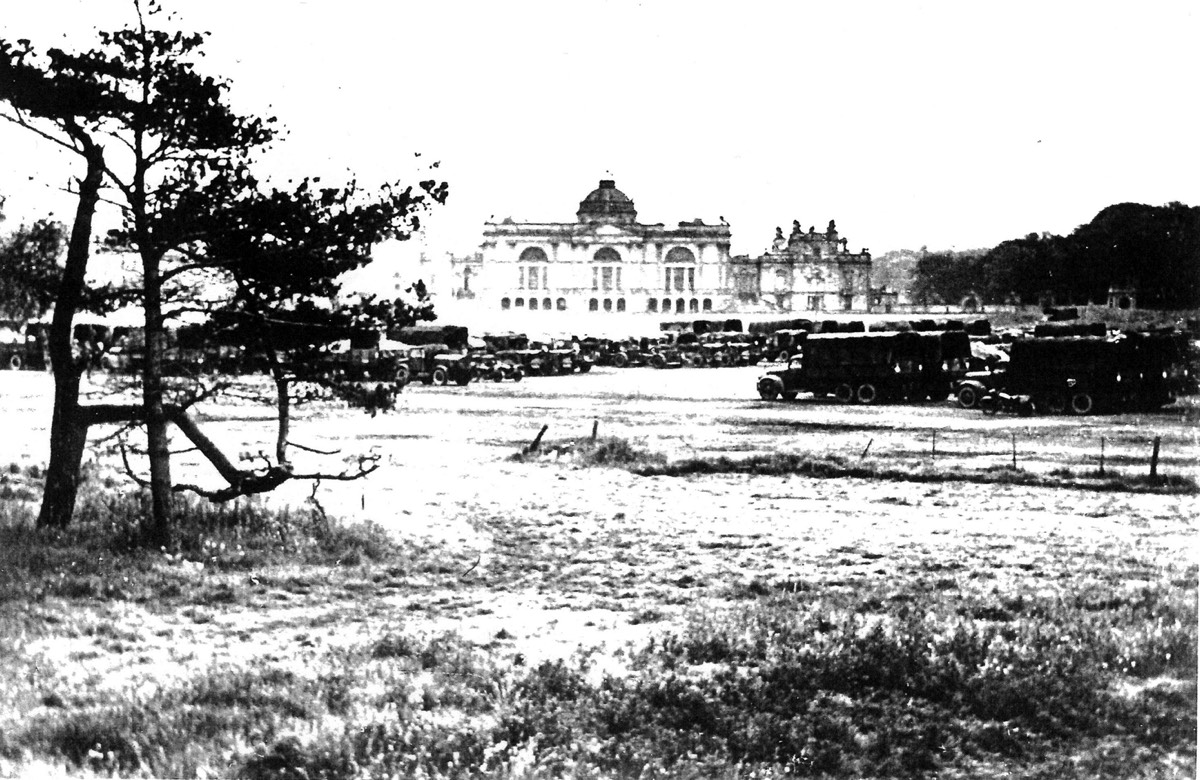

The Ist Motorised Artillery drawn up for inspection in front of Gosford House.

A series of photographs of the same inspection of the Polish artillery regiment in front of Gosford House. Major Bozyslawski, C.O. of Ist Polish Motorised Artillery regiment is second from the right. General Maczek is the inspecting officer, fourth from right.

Training In The Lammermuirs

We trained in the Lammermuirs with shooting once a month when we used to go there. We couldn’t use too many shells but we had to train the gunners. The Lammermuir shepherds had to move the sheep away from our shooting area but the sheep came back and many were killed. We trained as far away as Kelso. When we came into action we proved this time wasn’t wasted. We were very, very efficient. We used to exercise with the tank regiment from Haddington and with an infantry regiment, I think, from the Borders. Lots of exercises.

The regiment leaves Gosford.

To Whitburn: Sneaking Into The Exclusion Zone

Before D-Day we had to move from Gosford to Whitburn, where the commandos had to train, because the conditions were like the ones we would face in Normandy. The whole area from Prestonpans, the Royal Musselburgh golf course, to North Berwick, the Coal Road right up to Haddington, the top road, was a forbidden area, a military zone. You had to have a special pass. My wife-to-be, who was in the ATS living in Edinburgh, had to get a pass when she wanted to come to visit her mother inside the zone. I managed to bluff my way into the zone a number of times when I came with my wife on a bus going into the zone. The military police would come on the bus and check everyone’s papers and they would ask me where I was going. I knew very little about North Berwick but I said I was staying at a hotel there which had been taken over by the military. I did this a number of times.

We stayed at Whitburn for perhaps two or three months. Montgomery came and made a speech. I had photos but they’ve been lost. We went to Filey in Yorkshire for perhaps a month and from Filey we moved to Southampton, I think. We were put into woods in tents. ENSA was performing day and night. There was lots of praying. After D-Day on the sixth of June, I had to get a special licence to get married on the tenth.

To France

One night we were loaded onto boats and taken to France. They were fighting for Caen at that time in July. Our division was part of the Canadian army and the air force bombed us. [Operation Goodwood] The Canadians were in a field on our left and the main body was on the road and my truck was in a field away from the road. We could hear the bombers coming: I think it was just after lunch.

The first lot of bombers went and dropped their bombs where they shouldn’t have and the smoke from this drifted and the second wave looked as though they were going to bomb it and us. I was stripped to the waist and I grabbed my tunic and ran away and tumbled into a ravine where there were plenty of other soldiers already. The Canadians suffered the most casualties because they didn’t have anywhere to escape to. We had only one casualty in our regiment, a fellow who couldn’t stay in his hole. He ran from hole to hole and was caught in the open by the blast. It was terrible. I was lucky. A warrant officer was checking who had been hurt and when I came back he said, ‘Where have you been?’ So I told him and he said that was alright. I play golf and after the war I met a fellow golfer, Tom Evans, who was just on the other side of the road!

Tadeusz waiting to cross the Rhine. He is just visible as the driver of the Bren Gun Carrier (wearing goggles).

We moved on after Falaise. That was another bad time. I wasn’t involved but I was driving a truck used to start other trucks with jump leads, a special truck. I was in LEDs., a tracked vehicle with batteries in the back. It was a waste of my efforts. I did have to help others but for all the time I was in this I was only asked to help about a dozen times. It was most unpleasant as the truck didn’t have any protection or cab and the rain was absolutely terrible. I complained and asked to be transferred and I was, to a Bren Gun carrier and there was no protection in that either!

We eventually came to Germany and I was transferred to driving lorries and all sorts of vehicles. I ended the war in Wilhelmshaven. We had fought with the tank regiment which had trained in Haddington and had all sorts of other elements in our Division.

The interviewer told Tadeusz about General Majeck having a hard time in Gifford after the war. Tadeusz said, “... he had caught a bus in Edinburgh and sat near a chap he thought he knew. He got up and said, ‘are you ….?’ and it was the Colonel of my regiment. He said I could give you a job but I said I already had a job. I was a fitter/turner and got jobs easily.

I stayed in Germany for two years after the end of the war because they didn’t know what to do with us. For about six months I was working in a British hospital in Germany as an interpreter and we got on very well with the British. The hospital was run by Dr Robertson. Once I borrowed skates and went skating on a fishpond in front of the hospital. This Colonel saw us and he organised the staff and nurses to go on a skating outing with sandwiches and so on. We skated all afternoon on some German lake. We played ice hockey and this British sergeant crashed into me and he broke his leg. I was a Lance Corporal. I didn’t advance any further because I wasn’t a soldier soldier just a civilian in uniform.

Into Germany

We eventually came to Germany and I was transferred to driving lorries and all sorts of vehicles. I ended the war in Wilhelmshaven. We had fought with the tank regiment which had trained in Haddington and had all sorts of other elements in our Division.

The interviewer told Tadeusz about General Majeck having a hard time in Gifford after the war. Tadeusz said, “... he had caught a bus in Edinburgh and sat near a chap he thought he knew. He got up and said, ‘are you ….?’ and it was the Colonel of my regiment. He said I could give you a job but I said I already had a job. I was a fitter/turner and got jobs easily.

I stayed in Germany for two years after the end of the war because they didn’t know what to do with us. For about six months I was working in a British hospital in Germany as an interpreter and we got on very well with the British. The hospital was run by Dr Robertson. Once I borrowed skates and went skating on a fishpond in front of the hospital. This Colonel saw us and he organised the staff and nurses to go on a skating outing with sandwiches and so on. We skated all afternoon on some German lake. We played ice hockey and this British sergeant crashed into me and he broke his leg. I was a Lance Corporal. I didn’t advance any further because I wasn’t a soldier soldier just a civilian in uniform.

I Settle In East Lothian

Some went back to Poland but I didn’t go. My wife took a course learning Polish, she was quite keen to go to Poland but while I was in Germany I learnt the situation in Poland and said no we’re not going. I settled in East Lothian where I knew some other Poles who stayed on.”